Breaking News

Lynnwood honors outstanding leaders during first-ever Chamber of Commerce gala

Story and photos by Nick NgLynnwood Today staff reporter Orginal Article: https://lynnwoodtoday.com/lynnwood-honors-outstanding-leaders-during-first-ever-chamber-of-commerce-gala/ Published: September 21, 2024 The Lynnwood

...0‘Sitting on a gold mine’: As change comes to Lynnwood, urban growth spurs debate

By Daniel Beekman Seattle Times staff reporter Orginal Article: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/sitting-on-a-gold-mine-as-change-comes-to-lynnwood-urban-growth-spurs-debate/ Published: May 22, 2022 at 6:00 am Updated May

...0Urban Land Institute visits Lynnwood for a parks study

The Urban Land Institute (ULI), in partnership with The Trust for Public Land (TPL) and the

...0Mayor Smith and Lynnwood City Council present Honoring Excellence Awards

LYNNWOOD, Wash., November 30, 2021 – Yesterday, during its regular Work Session, Lynnwood City Council and Mayor Nicola

...0Anna’s Home Furnishings re-interpreting what it means to be essential.

Snohomish County needs to see drastic decrease in COVID-19 cases to head to Phase 2. The

...0Anna’s Home Furnishings battles to be deemed essential

As the state of Washington has ordered the closure of all they consider nonessential to slow

...0

‘Sitting on a gold mine’: As change comes to Lynnwood, urban growth spurs debate

Print this article

Font size -16+

By Daniel Beekman

Seattle Times staff reporter

Orginal Article: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/sitting-on-a-gold-mine-as-change-comes-to-lynnwood-urban-growth-spurs-debate/

Published: May 22, 2022 at 6:00 am

Updated May 22, 2022 at 12:42 pm

LYNNWOOD — When Phong Nguyen’s parents opened a furniture store 24 years ago, they had no idea that a light-rail station would be built down the block, that the surrounding strip malls would be rezoned for high-rises and that the Puget Sound region would grow by more than 1 million people.

They just wanted to sell couches and dining sets.

But Lynnwood is evolving, says Nguyen, who now runs the store and lives minutes away. The station is scheduled for completion in 2024, thousands of apartments are sprouting and local politicians are agonizing over whether to welcome thousands more to this sleepy suburb north of Seattle.

In a meeting last month, one City Council member warned against “too much housing,” while another reminded his colleagues that a busy, walkable core is what many constituents “have long asked for.” The debate matters partly because the region’s taxpayers are investing $3.1 billion to add light rail from Northgate to Lynnwood, with a $5.7 billion extension to Everett also planned. Respondents to a recent Sound Transit survey about a site the agency controls next to the station requested mixed-income, family-size apartments and shops there.

Nguyen, 44, who’s volunteered with Lynnwood’s food bank and police department, says the burgeoning “City Center” area could become a satellite for tech jobs, especially with hybrid work. In the meantime, real estate developers are sniffing around Anna’s Home Furnishings, located on 1.28 acres that the Nguyens own. The family could make a deal, or stay put and sell beds to the apartment dwellers moving in.

Either way, Nguyen believes, “We’re sitting on a gold mine.”

The changes accelerating in Lynnwood, population 39,000, are like those occurring in many communities where Sound Transit is expanding service. Though Bellevue and Redmond on the Eastside are years ahead, Snohomish County cities must also add jobs and apartments to help address the climate crisis and housing crunch, said Josh Brown, executive director of the Puget Sound Regional Council, which has determined that about 70% of growth through 2050 should happen along transit corridors.

Some characteristics set Lynnwood apart. Situated where Interstate 5 and Interstate 405 converge, it grew in the 1960s and 1970s into a car-centric shopping destination, with Alderwood mall opening in 1979. Furniture stores clustered nearby, which is why Nguyen’s parents, refugees from Vietnam, started their business in the area.

After college, Nguyen had a career in Silicon Valley. He returned in 2005, as Lynnwood’s leaders began planning a metamorphosis. They rezoned 250 acres for buildings up to 350 feet tall, envisioning people of all ages living and working above restaurants, boutiques and pubs. At the same time, they vowed to preserve outlying neighborhoods for houses with yards.

The planning continued after voters in 2008 approved Lynnwood’s light-rail extension, which will carry passengers to downtown Seattle in 28 minutes. Still, the city’s population grew just 8% from 2010 to 2020. Only now does development at last appear to be ramping up, stirring excitement and anxiety.

“Growth pain”

Back in 2012, Lynnwood’s leaders passed legislation that preapproved environmental reviews for certain City Center projects, in an attempt to save time and entice developers. They also set limits on growth, capping the preapprovals at 3,000 housing units and capping overall construction in the area at about 9 million square feet.

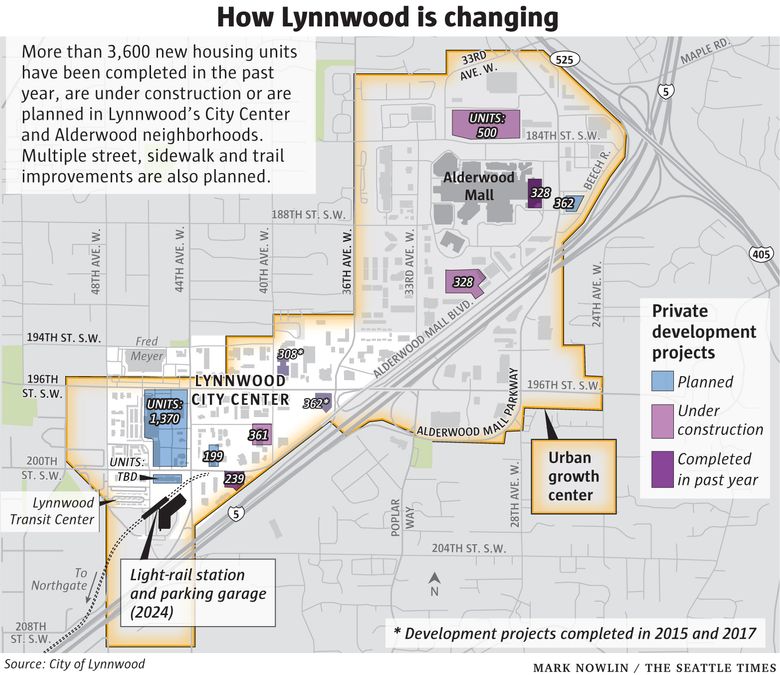

Those thresholds were based on 20-year projections, but more than 3,200 units already have been built, are under construction or are planned, according to Karl Almgren, Lynnwood’s City Center manager. Another 1,000 are open or coming soon at Alderwood, wedged beside the mall.

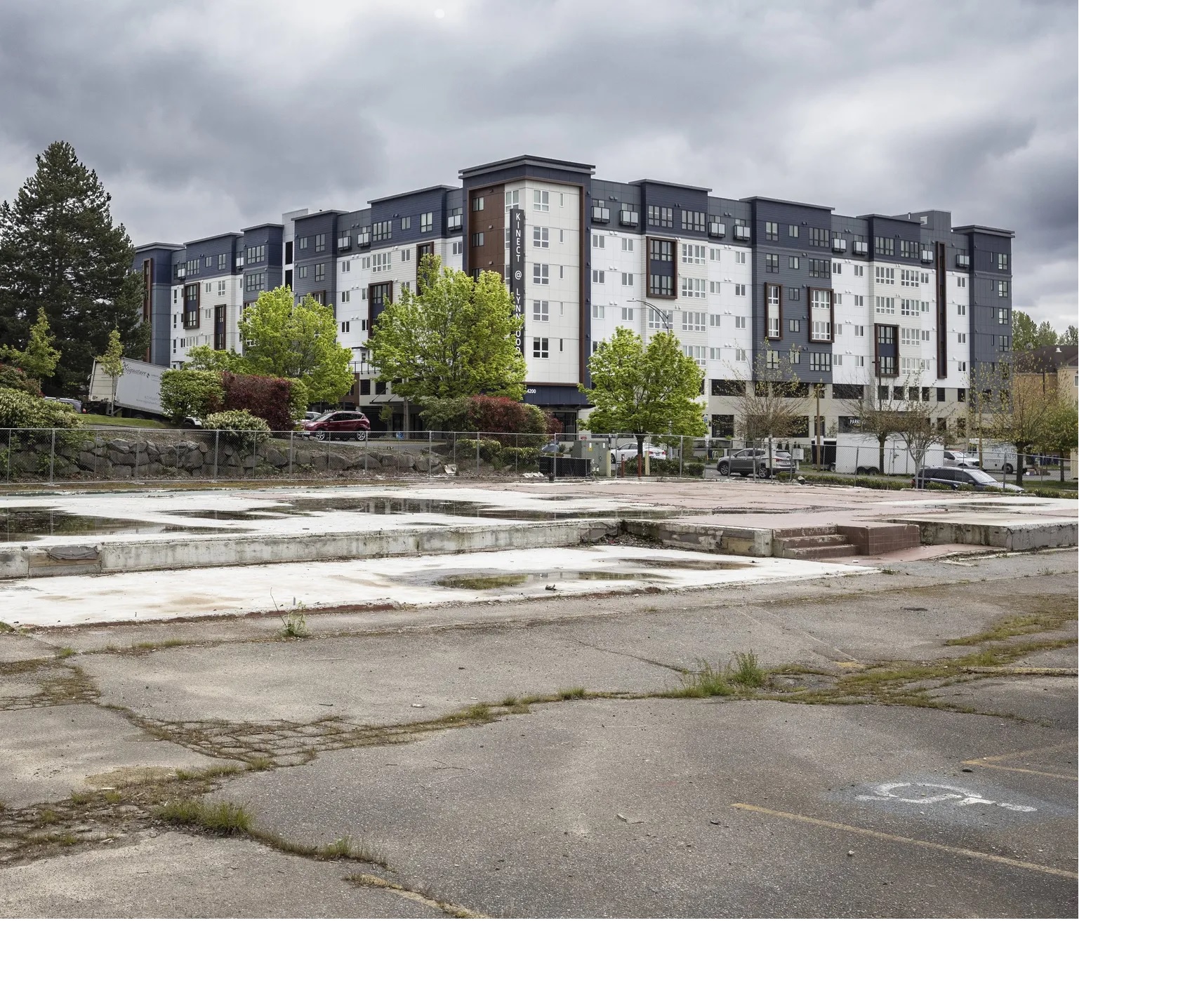

City Center today is a work in progress. The developer behind its most important project — a huge complex called Northline Village — is still looking for partners and has yet to break ground, Almgren said during a stroll past boarded-up windows and empty parking lots. But you can imagine what’s possible, he said, pointing down 198th Street Southwest, which is slated to be rebuilt as a promenade lined with businesses like cafes that the city is requiring developers to include on certain blocks.

“These sidewalks are going to be 16 feet wide,” said Almgren, who recently presented a proposal that would lift the preapproval cap to 6,000 units and eliminate the cap on overall development.

Leaving the current limits intact could discourage builders and stunt City Center’s metamorphosis, he said at an April 25 City Council meeting (first covered by The Urbanist) that flared after a public commenter railed against the proposed adjustment.

“How many units do we need … before somebody says stop?” former Councilmember Ted Hikel asked, suggesting more growth would strain public services like police and could “destroy the city by turning it into another Seattle, turning it into another Ballard.”

Boosters like ex-Mayor Nicola Smith, who retired last year, say dense housing can create a vibrant environment in which to “live, work and play” — and generate tax revenue. Lynnwood needs gathering places, agreed Zerai Mahangel, waiting to meet his nephew at a Starbucks on 196th Street Southwest packed with people tapping on laptops and chatting.

“Sometimes I see older people hanging out (at the food court) in the mall,” because there aren’t many other options, said Mahangel, 66.

Yet multiple council members echoed Hikel. Lynnwood is already “doing our part” growth-wise, Shannon Sessions said, and a 6,000-unit target would do “absolutely nothing” for existing residents, Jim Smith added.

“This will increase traffic. This will increase crime,” without advancing affordability, he said, arguing developers would be the “real winners.”

“There’s no mandate that Lynnwood has to accommodate every person who wants to move to the Pacific Northwest,” said Patrick Decker.

Across the council dais, Josh Binda shared mixed thoughts and George Hurst signaled support for the proposal, clouding the political picture ahead of a vote that’s been postponed.

There are real concerns, said Binda, who along with Decker was elected last year. Nonetheless, “People are going to come to Lynnwood. We’re going to need more housing,” he added.

The city can adapt, Hurst said. Major improvements to streets and sidewalks are underway. A “town square” park is planned. A creek will be daylighted by the light-rail station.

“We’re in the growth pain portion of this,” Hurst said.

Raja Akhter understands the pros and cons better than most, said the business owner, whose store across from the light-rail station sells South Asian, Middle Eastern and Mexican groceries. Two years ago, Sound Transit said JD’s Market would have to move, panicking Akhter, he recalled.

The agency wanted access to the store’s parking spots to offset spots lost during light-rail work at Lynnwood’s bus terminal, Sound Transit spokesperson John Gallagher said. JD’s was going to have to move eventually anyway, to make way for Northline Village.

The store snagged new digs close by and Sound Transit has paid $700,000 in relocation assistance so far, with the process slowed at times by due-diligence steps, Gallagher said. But the agency hasn’t used the parking spots yet and JD’s has been stuck paying double rent while renovating its new location and wrangling with Sound Transit over reimbursements, said manager Mohamed Elshabik.

“They keep delaying, delaying,” Akhter said.

Even so, Akhter is bullish on Lynnwood. Assuming JD’s survives, he expects new residents and light-rail riders to bolster his diverse customer base. Almost two-thirds white in 2010, the city’s residents were almost half people of color by 2020.

Some people moving to City Center are newcomers and others, like Evan Primm, have local roots. Primm, 28, works for Edmonds School District and rents a 2-bedroom apartment at a building called Kinect@Lynnwood that opened a few months ago.

“My parents live pretty close. I grew up here,” he said. “Long term, the challenge is saving for a house.”

Lynnwood’s new units could attract bargain seekers from Seattle, though Primm and his roommate pay plenty: $2,135 per month. Rents for older, low-rise apartments near the light-rail station are bound to increase, said Carrie Siemering, who moved to the Collins Junction complex “because it was the most affordable I could find.” By the time City Center becomes trendy, “I’ll be gone,” predicted Siemering, 54, who works two jobs to cover her $1,500 monthly rent.

Matthew Gardner, chief economist at Windermere Real Estate, doesn’t expect to see development above 12 stories in City Center anytime soon. High-rises are still cost-prohibitive in a market like Lynnwood, he said.

But the area has the right “bones” for lots of growth, Gardner said, and Lynnwood should “be bold,” added Brown from the Regional Council, because bus-rapid transit lines will speed passengers to Mill Creek and the Eastside starting in 2024 and 2027, respectively, and because City Center’s strip malls can be redeveloped without directly displacing residents. Nguyen has lobbied for smoother business permitting.

“Something spectacular”

Nicola Smith, the ex-mayor, said she worries that “NIMBY-ish” politics may stall Lynnwood’s nascent momentum. Whereas Nguyen, who stands to gain as much as anyone, is undaunted. When he talks to local leaders, he tells them City Center could be studded with rooftop gathering spaces, boasting panoramic views. He says, “We have the opportunity to do something spectacular here.”

This coverage is partially underwritten by Microsoft Philanthropies. The Seattle Times maintains editorial control over this and all its coverage.

Daniel Beekman: 206-464-2164 or dbeekman@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @dbeekman. Seattle Times staff reporter Daniel Beekman covers politics and communities.

Related Articles

Snohomish County businesses worry about another potential lockdown as COVID cases surge

With coronavirus cases surging in Washington for the third time, the Snohomish County Executive said it’s not impossible for another

Anna’s Home Furnishings re-interpreting what it means to be essential.

Snohomish County needs to see drastic decrease in COVID-19 cases to head to Phase 2. The county averages about 300

King5 – Growing up in Snohomish County: Lynnwood’s changing landscape

The city of Lynnwood is continuing to grow, and with tons of new development in the works, it’s bound to

No comments

Write a comment

No Comments Yet!

You can be first to comment this post!